The Cornucopia Institute recently sat down with Dr. Charles Benbrook to discuss pesticides. He has spent 50 years researching their impacts on our health and the environment and advocating for change. He worked on the House Committee on Agriculture and for the National Academy of Sciences and played an important role in the Food Quality Protection Act of 1996, which aimed to change the way EPA regulates pesticides to better protect children’s health.

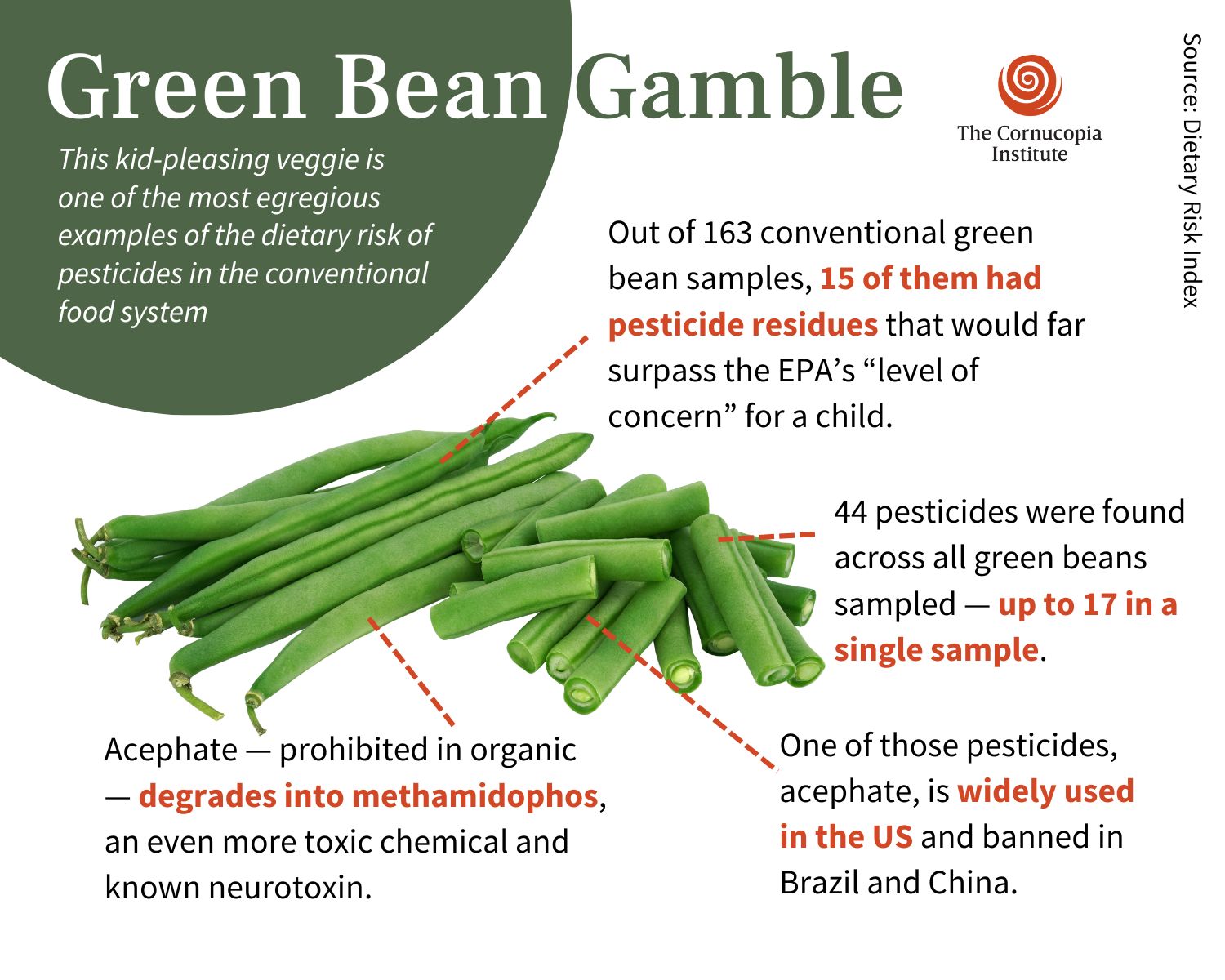

Benbrook’s work has culminated in a sophisticated system for quantifying the risk of pesticide residues in our diet. Called the Dietary Risk Index (DRI), it could significantly advance how regulators measure and comprehend the human-health implications of pesticide use — “like going from a rotary phone to an iPhone 15 in one step,” he says.

Fueled by a dataset comprising 125,000 food samples, the DRI is a much-needed tool for undermining the tactics used by the chemical industry.

How does the DRI compare to other systems used to assess pesticide dietary risk?

There is no other system like it. It shows the ratio of pesticide exposure in one serving of food relative to the maximum acceptable daily dose determined by the EPA, a threshold that considers the impact of lifetime exposure. Users can aggregate risk levels of multiples residues in a particular food and slice and dice data to show pesticide dietary risk in imports versus domestic and organic versus conventional food.

Isn’t the EPA already tracking this?

No, it is not. The EPA’s job is to set hopefully “safe” tolerance levels covering residues of a single pesticide in all the foods on which a pesticide is applied.

But the EPA, and regulators worldwide, lack a system to comprehensively appraise dietary risk levels and trends across foods, pesticides, productions systems, and countries of origin. They surely need such a system.

What does the DRI data say about how conventional and organic produce differ in potential chemical exposure?

There’s a huge difference. There are a few hot spots of pesticide risk in imported organic – for example, frozen cherries from Turkey and some of the spices and food ingredients coming from Southeast Asia. But it’s safe to say that overall, both domestically grown and imported organic food eliminates most of the pesticide risk in the US food system, especially in fresh fruits and vegetables.

The science is clear. So why isn’t this widely accepted by the general public?

Unlike many European consumers, the US public does not understand the enormous human health and environmental benefits stemming from organic food and farming. Why? Because USDA policy still asserts that organic food is neither safer nor more nutritious. The other enormous institutional constraint arises from the fact that researchers can’t get public funding nor publish findings about the human health benefits of organic food without triggering the immune system of “US Ag Inc.” I’ve seen it happen many times. The agribusiness and food companies that are profiting from our current high-volume, low-quality industrial food system have captured the keys to the city, and they’re not going to hand them over without a fight.

Which groups are the most vulnerable to the pesticide risks in our food supply?

The most serious risks come during the two bookends of life: infancy and childhood and older adulthood. The science pointing to pesticide-exposure impacts on children’s neurodevelopment is regrettably solid now, and new evidence of adverse impacts on metabolic health among children is deeply worrisome.

There are many reasons why organic food enhances the health of aging Americans. Our bodies’ ability to produce indigenous antioxidants weakens as we age and as our immune systems get rusty. Both unavoidable consequences of aging underscore the importance of nutrient-dense food. A lot of food isn’t palatable to older people, who struggle to get enough nutrients from the few foods they consume regularly. But you can make a healthy, delicious diet out of fresh organic berries, broccoli, beans, spinach, and dairy products. Antioxidants delivered through organic food fight inflammation, which is linked to most of the mental diseases of aging. And if you’re combating cancer, organic food cuts exposures to chemicals that trigger or promote tumor growth.

What is your plea to policymakers for acting on this information?

There’s an important window of opportunity in the current Farm Bill cycle. I hope Congress will convince the National Organic Program (NOP) to adopt a new application of the DRI we call OrgTracker, which has received encouraging interest among certifiers. OrgTracker would take the pesticide residue data that the NOP requires certifiers to collect and run it through the DRI. If the NOP developed new, rapid-response enforcement capabilities and deployed OrgTracker to target growers shipping organic food with questionable and/or illegal residues, the organic community could quickly eliminate 90% of the already very low pesticide dietary risk from certified organic food. That is how the NOP and organic community can retain consumer confidence in the integrity of the USDA organic seal.

The above is an excerpt, the full-length interview can be found here.

This article was originally published in the summer issue of The Cultivator, Cornucopia’s quarterly newsletter. Donate today, and we’ll mail you the fall issue, filled with stories you won’t find anywhere else.