by Kestrel Burcham, JD

Farm and Food Policy Analyst at The Cornucopia Institute

Introduction to Organic Livestock and Grazing Requirements

How organic livestock are produced is covered by specific regulations—the only such federal regulations concerning a food product that address how the animal was raised and not just the qualities of the final product.

|

The Organic Foods Production Act (OFPA), published regulations, guidance from the USDA, and certifier inspections all play a part in how organic livestock are produced. However, the regulations form the basic structure for how everything plays out in the “field”; those regulations will be the focus of this article.

Basic Regulatory Requirements for All Organic Livestock

All organic livestock must be provided with year-round access to the outdoors, shade, shelter, exercise areas, fresh air, clean water for drinking, and direct sunlight.[1] Each of these provisions can be adjusted for the specific needs of the species, how old the animal is, the regional climate, and the environmental needs of the area. Pasture is only required for ruminant livestock.

The pasture itself must be managed as a crop in full compliance with the organic standards.[2] As an organic crop, this pasture cannot have pesticides, herbicides, or synthetic fertilizers applied to it. Additionally, any land that is specifically managed for feed value in livestock grazing must also maintain or improve soil, water, and vegetative resources.[3]

Livestock may be “temporarily” confined, and regulations lay out the specifics of how and when this may be done.[4] In general, the regulations allow for confinement due to things that would put an animal’s health or well-being at risk, or where their being outside would put soil or water quality at risk.

Ruminants Have Special Considerations

Ruminants are a broad group of animals, including cattle, goats, sheep, antelope, and deer. In general, the group is classified by the animals’ ability to acquire nutrients from plant-based foods by fermenting it in a specialized stomach (the rumen).[5]

Due to past abuses (where some producers were confining animals instead of grazing them), ruminants get more coverage in the current organic regulations than any other livestock group. For example, ruminants may be confined in a greater number of situations.[6] Specific rules for temporary confinement are just the beginning: ruminants also have particular rules dictating how much of their diet must be derived from pasture.

The Pasture Rule

A Brief History

The “pasture rule” refers specifically to the minimum requirements for grazing ruminant livestock for organic production. This set of rules was introduced by the USDA in 2010 and incorporated minimum benchmarks for time spent on pasture and proportion of diet provided through grazing. This was a result of years of agitation by The Cornucopia Institute, their farmer-members, and urban allies.

The intended effect of this rule addition was to bring into compliance a handful of giant factory dairies that were abusing the spirit and letter of the organic law by confining milking cows for most of their productive lives.

The exceptions carved out within the pasture rule sections make it clear that the grazing requirements are most applicable to dairy animals: organic slaughter stock do not need to be finished on pasture or meet the minimum percent grazing requirement.[7] This exception means that organic beef animals can be finished with organic grain in feedlots.

The updated livestock regulations became effective 120 days after publication, in June of 2010. Operations that were already certified organic had one year to implement the provisions. However, dairies that obtained organic certification after the effective date were expected to demonstrate full compliance immediately.[8]

By enacting these changes, the USDA confirmed that pasture was one of the foundations of organic dairy and other ruminant livestock production. The new rules were designed to make it easier for organic certifiers to confirm compliance.

What Do the Pasture Rule Regulations Mean?

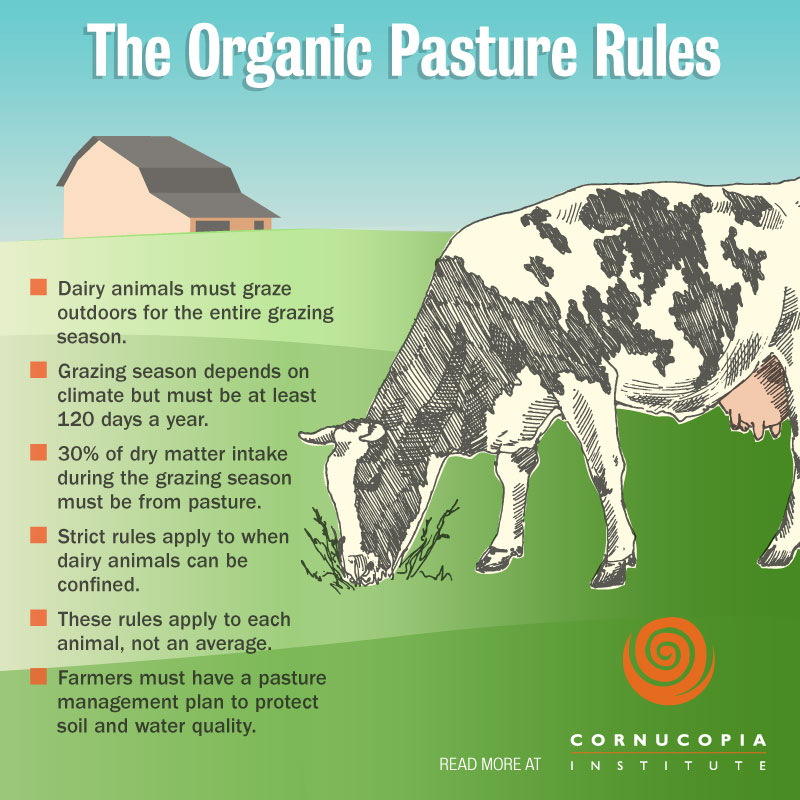

In short, the pasture rule lays out several strict requirements, dictating that all ruminants must:

- Be provided pasture that is managed in a way compliant with organic regulations for crops;[9]

- Only be confined temporarily, and only for reasons laid out in the regulations;

- Be grazed on organic pastures for the duration of a region’s grazing season;

- Be provided a specified minimum amount of feed intake from pasture, on average, over the course of a year.[10]

There are many regulations within the general livestock standards that dictate how organic pastures and ruminant livestock are managed, but the last two points are what is generally referred to as the “pasture rule.” These requirements focus on dairy herds and not slaughter stock.[11]

Cornucopia filed formal, well-documented legal complaints against specific organic “factory” dairy operators abusing this provision. To date, the USDA’s National Organic Program has failed to take enforcement action.

Dry Matter Intake and Grazing Seasons

The regulations on livestock living conditions[12] note that ruminant dairy animals “[m]ust be scheduled in a manner to ensure sufficient grazing time to provide each animal with an average of at least 30 percent “dry matter intake” (DMI) from grazing throughout the grazing season.”[13]

The organic pasture practice standard echoes this requirement,[14] stating that producers must manage pasture in compliance with organic regulations “…to annually provide a minimum of 30 percent of a ruminant’s dry matter intake (DMI), on average, over the course of the grazing season(s)…”[15] As explicitly stated in other language, these standards allow up to 70% of a ruminant animal’s diet to come from non-pasture feed such as hay, grain, or silage.[16]

DMI is defined as the “[t]otal pounds of all feed, devoid of all moisture, consumed by a class of animals over a given period of time.”[17] In simple terms, DMI is a way to calculate how much feed an animal is actually consuming by calculating its weight after all water is removed from the feed. This calculation is important to livestock producers because fresh grass or other living plant material generally has much more water than dried feeds such as hay, silage, or grain. DMI is useful because the raw weight of feed can be misleading; a given weight of fresh grass would not have nearly as much caloric value as the same weight in dried hay or grain, because the grass includes so much water.

Producers are required to calculate DMI as an average over the entire grazing season for each type and class of animal.[18] A producer who raises both goats and cattle, for example, has to make calculations for those animals separately. In fact, other sections of the regulations make it clear that each individual animal must meet the average of 30% DMI requirement. This means that producers cannot average the DMI across a herd, allowing some animals (such as young heifers not old enough to be milked) to graze 100% of the time to make up for dairy cows that never see a blade of grass.[19]

The length of the grazing season is another important aspect of the pasture rule. Ruminants must be grazed throughout the entire grazing season, which will vary based on the regional climate and seasonal weather patterns. However, even taking climate variation into account, organic regulations require the grazing season to be a minimum of 120 days per calendar year.[20] This grazing season does not have to be continuous, and can be broken up within the year to suit a producers’ needs..

Producers must manage the grass throughout the season so that animals can actually graze during that time; just having animals outside in an overgrazed lot will not meet organic requirements.[21]

Producers are also required to keep close records on their animals, including their DMI calculations and details about their particular pastures, such as the type of forage growing there, how many animals are grazed, and how they are protecting soil and water quality. These “pasture management plans” must be updated annually if any changes are made.[22]

Cornucopia’s Organic Dairy Scorecard helps consumers determine which brands come from the highest integrity farmers. Many of the best organic dairy producers provide far more than 30% (up to 100%) of their cows’ diet from fresh pasture.

How Harsh is the Pasture Standard?

The pasture requirements for organic livestock are not difficult to meet. The 30% DMI requirement and minimum 120-day grazing season for each individual animal is a low bar for animals that evolved to get all their nutritive needs from grazing alone. This standard should be easy to meet in most places in the U.S., even those with very arid climates. To comply in challenging environments, many operations have to irrigate their land and must carefully balance their available acres of pasture and number of cows.

One hundred twenty days of grazing time is only one-third of a year. Even in northern states with long, cold, and snowy winters, like Wisconsin, farmers can keep their cattle out on well-managed pasture for 200 days or longer.

In wetter climates like portions of Oregon and Washington, cattle may only be kept under a roof for four months at most during periods of heavy rainfall. Pasture quality degrades rapidly when the land is saturated with water, and grazing cattle can cause serious environmental damage during this time.

In most areas of the U.S., cows can easily average at least 50% of their DMI from well-managed pasture during the season. As noted, enterprising dairy producers even meet the market demand for milk produced from only pasture and hay. These “100% grass-fed” producers represent a growing niche in the organic marketplace.

Conclusions

Studies show greater nutritive benefits come from pasture-fed dairy compared to conventional feedlot dairy.[23] What’s more, the organic seal warrants that the pasture was managed consistently with organic crop requirements.

Family farms tend to exceed the minimum grazing requirements laid out in the regulations to the benefit of the animals, environment, and the end consumer.

For those interested in dairies that go above and beyond the minimum grazing requirements, Cornucopia’s Organic Dairy Scorecard includes superb grazing practices in its rating criteria. For more information on the regulatory background, science, and history of organic dairy, interested readers can check out Cornucopia’s comprehensive report: The Industrialization of Organic Dairy.

References:

[1] 7 CRF § 205.239(a)(1)

[2] § 205.240(a)

[3] § 205.2. Pasture.

[4] §§ 205.239(b) and (c)

[5] ScienceDirect Website. 2018. “Topic: Ruminant.” Accessed October 25, 2018. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/ruminant

[6] § 205.239(c)

[7] § 205.239(d)

[8] “USDA Issues Final Rule on Organic Access to Pasture – News Release No. 0059.10.” February 12, 2010. USDA. Accessed August 29, 2016. https://www.ams.usda.gov/press-release/usda-issues-final-rule-organic-access-pasture

[9] By providing pasture in compliance with § 205.239(a)(2) and managing pasture to comply with the requirements of § 205.237(c)(2).

[10] § 205.240(b)

[11] See § 205.239(d)

[12] 7 CFR § 205.239

[13] § 205.239(c)(4).

[14] 7 CRF § 205.240

[15] § 205.240(b)

[16] § 205.237(c)

[17] 7 CFR § 205.2. Dry Matter Intake.

[18] [§ 205.237(c)(1)

[19] § 205.239(c)(4).

[20] § 205.237(c)(1) Livestock feed.

[21] § 205.240(c)(2)

[22] § 205.240(c)

[23] Schwendel B, et al. August 15, 2017. “Pasture feeding conventional cows removes differences between organic and conventionally produced milk.” Food Chemistry 229: 805–813. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308814617303059