In honor of the 30th anniversary of the Organic Foods Production Act, we asked some of the early champions of the modern-day organic movement to reflect on what the label means to them. See the complete essay series here.

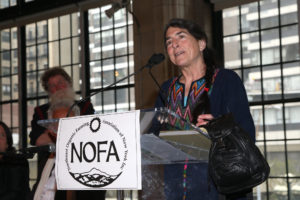

The following essay is by author and activist, Elizabeth Henderson. Henderson produced organically grown vegetables at Peacework Farm in New York for more than 30 years. A founding member of the Northeast Organic Farming Association (NOFA) in Massachusetts, she has been deeply involved in the organic movement since the 1970s. She serves on several boards and has been awarded many accolades at the state, regional, and national levels for her commitment to organic agriculture and food justice.

While the National Organic Program (NOP) came into existence with the Organic Foods Production Act (1990 Farm Bill), a longer milestone to celebrate in 2021 is the 50th anniversary of organic as a movement of farmers and conscious eaters to create an alternative to industrialized, chemical agriculture. Small groups of organic activists started NOFA and MOFGA in 1971. The next year, a few US citizens were among the founders of the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) in Europe. Organic farming and gardening are the modern adaptation of indigenous knowledge evolving in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Americas since the beginning of agriculture, a vital part of a globalized social movement of small-holder farmers and peasants that is dedicated to food sovereignty, social justice, gender equity and mitigating climate change.

To understand the role of the organic movement, I think it is important to situate it in the broader history of farming in the US. “Foodopoly: The Battle over the Future of Food and Farming in America,” by Wenonah Hauter, gives a vivid account of the transformation that took place over the past decades: “After World War II, farmers became the target of subtle but ruthless policies aimed at reducing their numbers…” (p. 12) From a country where over half the people lived on farms, in the US today there remains a tiny farm population with family-scale farms struggling to make a living in an economy dominated by increasingly consolidated corporations. Since the mid 1950s, corporate power has forced the federal government to abandon the policies that saved family-scale farms from the Depression and ended the Dust Bowl: the parity system based on price supports, supply management and mandatory conservation. With ever fewer markets and input suppliers, farmers are caught in an overproduction treadmill that leaves them dependent on government handouts for survival. The financialization of land markets has put the price of farmland way above what a farmer can afford from farm earnings. The wealth farmers produce is being transferred to Tyson, Cargill, ADM, Bayer/Monsanto, Amazon, Walmart. In 2020, a third of all farm revenues will come from taxpayer money, not from market payments. Cheap food has become the bedrock of US food policy and as a result, the farm crisis that ignited in the 1970s has yet to end.

The organic movement is one of the most effective ways farmers have found to respond to this crisis, saving some generational farms and allowing new ones, like mine, to come into existence. By adopting and codifying organic systems, farmers won the loyalty of environmentally conscious shoppers who were willing to pay a premium to support the farmers. Organic certification ensured the shoppers they were getting what they paid for. The NOP label added legitimacy, but not surprising in a capitalist food system, as soon as the big boys saw a profit center, they moved in, buying up many of the small companies that manufacture organic products. Since the NOP label appeared, the movement has been locked in arm wrestling with the industry over the integrity of the federal program. For the movement, organic must be true to the Principles of Organic Agriculture: grown in healthy soils, minimally processed, an entire supply chain where all participants – farmers, farm and other food workers as well as livestock – are treated with humanity and fairness. Add-ons to the NOP label – Food Justice Certified, the Real Organic Project, Regenerative Organic Certification – identify farms and brands that respect the Organic Principles of Ecology, Health, Care and Fairness. If the movement wins the arm wrestle, all of these values will infuse the NOP program cancelling profit-driven compromises and loop holes.

But what of the future? IFOAM predicts a 100% organic food system within 30 or 40 years. (See “Cultivated,” IFOAM NA newsletter.) I like this prediction, but I do not think it will mean 100% “certified” organic. The organic movement today is recognizing that our white dominated agriculture is an expression of colonial settler culture. The time has come to revise the organic cannon – Sir Albert Howard, Lady Balfour, Rudolf Steiner, Robert Rodale – to honor the contributions of our great African-American agronomists – Booker T. Washington, George Washington Carver, Booker T. Whatley – and to reconnect with the indigenous peasant origins of the integrated agroecological systems that make up organic farming. The white farmers of the organic movement in the US have been damagingly separated from these origins and great scientists/teachers. To reach 100%, organic farmers need to offer conventional farmers a message of hope – stop listening to Sonny Perdue’s whining that you have to “get bigger, or get out.” Just the reverse: get smaller, diversify, get more resilient, join our movement and stay in! Our organic social movement will gain strength from the world wide peasant movement for agroecology and food sovereignty and farmers will join with other working people to make fair food central to a Green New Deal.