Food Sentry continues its analysis of international food safety violations. We recently reported our initial findings after analyzing nearly 1,000 reported food violation incidents in 73 countries. Lab testing results from foreign sources were reviewed and our preliminary findings indicated that the top five countries with the most violations were China, United States, India, Vietnam and Japan.

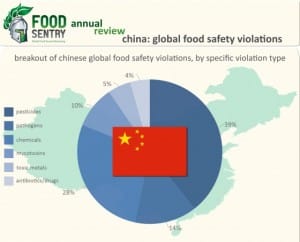

We are now analyzing information to determine which contaminants are most likely to be encountered by the consumer. Our first look is at China, which had the most violations of any single country. We looked at all contaminants reported and were able to pair many of them with certain types of food. For instance, produce was most likely to be contaminated with pesticides while seafood was most likely to be contaminated with antibiotics (see the expanded version of the infographic here).

China is a large trading partner with the US, and it is its largest trading partner when it comes to seafood. Any walk through a grocery store will turn up literally hundreds of items from China. Chinese foods get a lot of bad press, so it’s worth taking a look at some hard data to see what we can learn. Here’s what we found regarding contaminants discovered in various Chinese foods:

Pesticides were the number one problem, with 32 distinct pesticides found in Chinese foods, mostly in produce, fruit and spices. In one instance, a cumin sample had six different pesticides (acetamiprid, carbendazim, profenofos, cypermethrin, hexaconazole and Ethion) detected at violative concentrations in laboratory testing.

Pesticides were the number one problem, with 32 distinct pesticides found in Chinese foods, mostly in produce, fruit and spices. In one instance, a cumin sample had six different pesticides (acetamiprid, carbendazim, profenofos, cypermethrin, hexaconazole and Ethion) detected at violative concentrations in laboratory testing.

Antibiotics were a particular problem with seafood from China. We found multiple instances of leuco-malachite green (a metabolite of malachite green), enrofloxacin and ciprofloxacin (fluoroquinolone drugs), and sulfamethoxazole (a sulfonamide drug) contamination.

Leuco-malachite green/malachite green have been banned in aquaculture by the FDA since 1983 due to serious toxicity, so their continued use in Chinese aquaculture is cause for concern. It is actually a dye used in the clothing industry, but it has anti-bacterial properties that are effective for use in fish farming. In this case we found it reported as a contaminant in tilapia, grouper, mackerel, carp and crabs.

According to the National Fisheries Institute, tilapia was the fourth-most popular seafood in America in 2012, just behind shrimp, canned tuna and salmon. Over 75 percent of all the tilapia Americans consumed in 2012 came from China. According to the USDA Economic Research Service, that’s 286.7 million pounds!

Not all of that was contaminated of course, but since the FDA inspects only 2 percent of all food imports and tests much less than 1 percent, there’s a good chance that some contaminated tilapia is getting through.

The fluoroquinolone antibiotics are not allowed for aquaculture in the United States, but they are routinely detected in Chinese seafood products. Enrofloxacin and ciprofloxacin are used to control the spread of disease on fish farms, where bacterial infections can spread very quickly, depending on the farm type, due to very dense fish populations in nets and pens. The concern here is that bacteria will develop a resistance to these drugs if you ingest them regularly while eating fish, making them less effective for human use.

Sulfamethoxazole concerns are similar to those surrounding fluoroquinolones, where research has already discovered several Salmonella serotypes that are resistant to this drug, according to UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

Pathogens were found mainly in seafood, with Escherichia coli, Clostridium botulinum and unspecified coliform bacteria being reported multiple times. Typically, these types of pathogens find their way into the fish because of poor process control in preparing the fish for distribution. Detection of coliform bacteria typically indicates pathogens of warm-blooded fecal origin are present.

Various chemicals were detected in excess of approved amounts, including sulfur dioxide, other various unspecified sulfites, formaldehyde, coloring dyes, and sodium saccharine. Most concerning was the detection of sodium hydroxide in milk. Also known as caustic soda or lye, sodium hydroxide is used to regulate acidity in foods. At high levels, it can be extremely caustic. Milk products from China are currently not allowed import into the United States.

A wide range of mycotoxins were present, mainly in seeds, oils, dairy and rice. Mycotoxins are poisonous molds produced by various fungi. Six types of aflatoxins were reported as well as citrinin. Testing identified aflatoxin B1 in multiple samples of peanut oil, sesame seeds, Sichuan pepper, and peanuts. Additionally, aflatoxin M1 was identified in milk powder and milk samples, while citrinin was found in red yeast rice and red yeast rice powder.

Toxic metal contamination was found across a wide range of products, although not in a large number of samples. Excessive lead was found in kelp and cinnamon, cadmium in cinnamon, bamboo pith and crab, and mercury in infant formula. The US FDA does not routinely test imports for toxic metals, except mercury.

Economically Motivated Adulteration (EMA) continues to be an issue in China. EMA refers to the intentional adulteration of a food with a substance for economic gain. The best-known example of this in China was the addition of melamine to milk powder in 2008, where more than 50,000 infants were made ill by the ingestion of the substance. Nearly 13,000 hospitalizations and at least four deaths occurred.

We found multiple instances where seafood had water added to increase its weight. Sometimes this can increase the weight of the fish product by as much as 30 percent, depending on the species. This is done in a number of ways, but most often comes from soaking the fish in sodium tripolyphosphate (STPP), which at high concentrations can be toxic. Fish do not naturally retain water, but soaking flaky fish fillets, shrimp or crab meat will improve the appearance of the product as well as force it to absorb water. Since fish is sold by weight, this is a cheap way to improve profits. If you see a milky substance coming from your fish while cooking, or if the size decreases dramatically, your fish may have been ‘treated’ with STPP. It may be listed on the label, but the FDA does not require it.

Furthermore, you may not know that shellfish can be sold ‘wet’ or ‘dry.’ ‘Wet’ means it’s been soaked. Ask your fish seller if he knows if the product is ‘wet’ or ‘dry.’ Here’s a video of a Chinese fish processing plant where this practice is underway (the video is in Hebrew/Chinese, but with English subtitles).

Other examples of EMA that were discovered in testing were counterfeit eggs (man-made from various substances and chemicals), synthetic shark fin, synthetic abalone and counterfeit peanut oil made from other oils. None of these products are likely to find their way to the United States. They are mostly sold at local markets, although the fake eggs have been exported to Indonesia.

Since China is one of the largest exporters of food to the United States, especially seafood, their performance in regulating their food production activities is of real consequence to the United States. The FDA has established three offices in China (Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou) with about a dozen people to begin to work with the Chinese to introduce better processes for identifying and reducing food risk so as to get an early start on producing safe food. Learn more about FDA’s efforts in China here.

Our initial analysis is based on a limited sample of data collected over 15 months. We are currently doing comparability studies with disparate data sources to discover whether the results we are seeing are typical for testing of Chinese food products. At this point, consumers are advised to exercise routine caution when deciding to purchase Chinese food products. Seafood represents the highest risk, although we cannot say precisely how much Chinese seafood may be contaminated. Our caution is based on the fact that very little of the total import amount is actually inspected and tested, and the results from foreign laboratories that do test demonstrate some persistent level of contamination across a range of products.