|

Consumer Reports’ new guidelines show you how to make the best choices for your health—and for the environment

Across America, confusion reigns in the supermarket aisles about how to eat healthfully. One thing on shopper’s minds: the pesticides in produce. In fact, a recent Consumer Reports survey of 1,050 people found that pesticides are a concern for 85 percent of Americans. So, are these worries justified? And should we all be buying organics—which can cost an average of 49 percent more than standard fruits and vegetables?

Experts at Consumer Reports believe that organic is always the best choice because it is better for your health, the environment, and the people who grow our food. The risk from pesticides in produce grown conventionally varies from very low to very high, depending on the type of produce and on the country where it’s grown. The differences can be dramatic. For instance, eating one serving of green beans from the U.S. is 200 times riskier than eating a serving of U.S.-grown broccoli.

“We’re exposed to a cocktail of chemicals from our food on a daily basis,” says Michael Crupain, M.D., M.P.H., director of Consumer Reports’ Food Safety and Sustainability Center. For instance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that there are traces of 29 different pesticides in the average American’s body. “It’s not realistic to expect we wouldn’t have any pesticides in our bodies in this day and age, but that would be the ideal,” says Crupain. “We just don’t know enough about the health effects.”

If you want to minimize your pesticide exposure, see the chart below. We’ve placed fruits and vegetables into five risk categories—from very low to very high. (Download our full scientific report, “From Crop to Table.”) In many cases there’s a conventional item with a pesticide risk as low as organic. Below, you’ll find our experts’ answers to the most pressing questions about how pesticides affect health and the environment. Together, this information will help you make the best choices for you and your family.

Learn about glyphosate, the most commonly used agricultural pesticide in the U.S. on farms.

How risky are pesticides?

There’s data to show that residues on produce have actually declined since 1996, when Congress passed the Food Quality Protection Act. This law requires that the EPA ensure that levels of pesticides on food are safe for children and infants.

Every year, the Department of Agriculture tests for pesticide residues on a variety of produce. In its latest report, more than half of the samples had residues, with the majority coming in below the EPA tolerance levels. “Conventionally grown fruits and vegetables are very safe,” says Teresa Thorne, spokeswoman for the Alliance for Food and Farming, an organization that represents growers of conventional and organic produce.

But that’s not the whole story. Looking at specific produce items, you see that progress has been made for some but not others. Grapes and pears, for example, once would have been in the high-risk or very high-risk categories but now rank low. But others, such as green beans, have been in the higher-risk categories for the past 20 years.

And there’s more to consider than just the amount of pesticides on the apple you eat. “Tolerance levels are calculated for individual pesticides, but finding more than one type on fruits and vegetables is the rule—not the exception,” says Urvashi Rangan, Ph.D., a toxicologist and executive director of the Consumer Reports Food Safety and Sustainability Center.

Our survey found that a third of Americans believe there’s a legal limit on the number of different pesticides allowed on food. But that’s not the case. Almost a third of the produce the USDA tested had residues from two or more pesticides. “The effects of these mixtures is untested and unknown,” Rangan says.

What’s the evidence that pesticides hurt your health?

A lot of the data comes from studies of farmworkers, who work with these chemicals regularly. Studies have linked long-term pesticide exposure in this group to increased risk of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease; prostate, ovarian, and other cancers; depression; and respiratory problems. There’s some suggestion that adults and children living in farm communities could also be at risk for chronic health problems.

The rest of us may not handle the stuff, but we are exposed through food, water, and air. The fact that pesticide residues are generally below EPA tolerance limits is sometimes used as “proof” that the health risks are minimal. But the research used to set these tolerances is limited.

In a 2010 report on environmental cancer risks, the President’s Cancer Panel (an expert committee that monitors the country’s cancer program) wrote: “The entire U.S. population is exposed on a daily basis to numerous agricultural chemicals. . . . Many of these chemicals have known or suspected carcinogenic or endocrine-disrupting properties.” Endocrine disruptors can block or mimic the action of hormones, even at low doses. “Endocrine effects aren’t sufficiently factored into the EPA pesticide-tolerance levels,” Crupain says. “And there’s concern they could cause reproductive disorders; birth defects; and breast, prostate, and other hormone-related cancers.”

Who may be at greatest risk from pesticide exposure?

Aside from farmworkers, it’s children. A child’s metabolism is different from an adult’s, so toxins can remain longer in a child’s body, where they can do more damage. Pesticide exposure can affect children’s development at many stages, starting in the womb. “Fetuses, babies, and kids are more vulnerable to the effects of pesticides because their organs and nervous systems are still developing,” says Philip Landrigan, M.D., director of the Children’s Environmental Health Center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York. And children’s risk is concentrated because they eat more food relative to their body weight than adults.

The health risks to children are significant. Even small amounts of pesticides may alter a child’s brain chemistry during critical stages of development. One study of 8- to 15-year-olds found that those with the highest urinary levels of a marker for exposure to a particularly toxic class of pesticides called organophosphates had twice the odds of developing attention deficit hyperactivity disorder as those with undetectable levels. Another study found that at age 7, children of California farmworkers born to mothers with the highest levels of organophosphates in their bodies while they were pregnant had an average IQ 7 points below those whose moms had the lowest levels during pregnancy. That’s comparable to the IQ losses children suffer due to low-level lead exposure.

The risk to adults is lower but still worrisome. “Pesticide exposure likely increases the risk, first, of cancerous tumor development, and, second, your body not being able to control a tumor growth,” says Charles Benbrook, Ph.D., a research professor at the Center for Sustaining Agriculture and Natural Resources at Washington State University and a consultant to Consumer Reports. In addition, research has linked endocrine disrupters with fertility issues, immune system damage, and neurological problems. “However, unlike cancer, quantifying those effects is difficult at this time,” Crupain says.

Does eating organic mean I won’t be eating any pesticides?

There are two groups of agricultural pesticides: synthetic and natural. Synthetics are created in labs, and natural ones are substances that occur in nature. The majority of synthetic pesticides (and all of the most toxic ones) used in conventional farming are banned in organic farming, but pesticide drift can mean chemicals sprayed on conventional crops may find their way to nearby organic farms. Still, all of the organic produce in our analysis fell into the very low-risk or low-risk categories.

USDA organic standards allow for the use of certain natural pesticides and very few synthetic ones. “But you can’t compare conventional and organic farming in an oranges-to-oranges kind of way,” says Michael Sligh, a farmer, founding chairman of the National Organic Standards Board, and Just Foods Program director at Rural Advancement Foundation International.

Natural pesticides are usually less toxic than synthetic ones. “ ‘Pesticide’ is a broad term used to refer to a range of substances from the very, very limited low-toxic ones allowed in organic farming to the highly toxic chemicals that can be used in conventional farming,” he says. “They are very different. Before a pesticide is even approved for use in organic farming, it must be evaluated for potential adverse effects on humans, animals, and the environment, and prove it’s compatible with a system of sustainable agriculture. And farmers must follow integrated pest-management plans that require that they use any approved organic pesticide as a last resort and develop strategies to avoid repeated use.” Those differences have implications for personal health but also for the health of farmworkers and the planet. “Folks need to understand the multiple benefits they are getting when they choose organic,” he says, “and the multiple choices they are making when they don’t.”

Some conventional farmers do follow pest-management plans similar to those of organic farmers. “Practices such as crop rotation and the use of beneficial insects or pheromones are tools both conventional and organic farmers use,” says the AFF’s Thorne. That may be so. However, Sligh says, “for organic farmers it’s a requirement, not an option.”

And eating organic means you may have fewer pesticides in your body. A study in Environmental Health Perspectives found that people who said they often or always ate organic produce had about 50 percent lower levels of organophosphate breakdown products in their bodies than those who rarely or never did. Those who sometimes chose organic produce had levels as much as 35 percent lower.

Should I skip conventionally grown produce?

No. The risks of pesticides are real, but the myriad health benefits of fruits and vegetables are, too. A 2012 study estimated that increasing fruit and vegetable consumption could prevent 20,000 cancer cases annually, and 10 cases of cancer per year could be attributed to consumption of pesticides from the additional produce. Another study found that people who ate produce at least three times per day had a lower risk of stroke, hypertension, and death from cardiovascular disease.

“We believe that organic is always the best first choice,” says Consumer Reports’ Rangan. “Not only does eating organic lower your personal exposure to pesticides, but choosing organic you support a sustainable agriculture system.” However, your primary goal is to eat a diet rich in fruits and vegetables—ideally five or more servings a day—even if it’s a type that falls into our very high-risk category. If organic produce is too pricey or not available, our analysis shows that you often have a low-risk conventional option.

Rules to shop by: Our risk guide for conventional produce

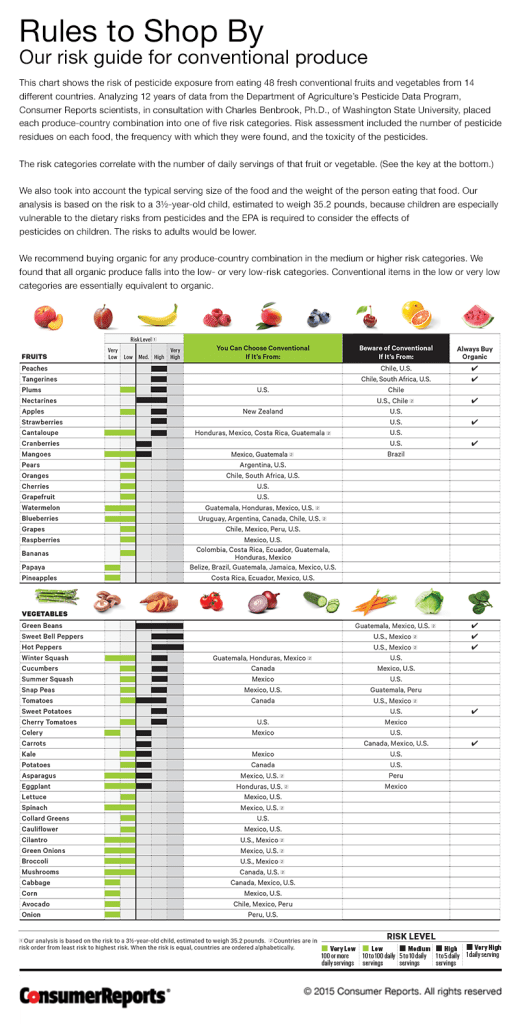

The chart below (download a PDF or click on the chart to expand it) shows the risk of pesticide exposure from eating 48 fresh conventional fruits and vegetables from 14 different countries. Analyzing 12 years of data from the Department of Agriculture’s Pesticide Data Program, Consumer Reports scientists, in consultation with Charles Benbrook, Ph.D., of Washington State University, placed each produce-country combination into one of five risk categories. Risk assessment included the number of pesticide residues on each food, the frequency with which they were found, and the toxicity of the pesticides. The risk categories correlate with the number of daily servings of that fruit or vegetable.

We also took into account the typical serving size of the food and the weight of the person eating that food. Our analysis is based on the risk to a 3½-year-old child, estimated to weigh 35.2 pounds, because children are especially vulnerable to the dietary risks from pesticides and the EPA is required to consider the effects of pesticides on children. The risks to adults would be lower. (Download our full scientific report, “From Crop to Table.”)

We recommend buying organic for any produce-country combination in the medium or higher risk categories. We found that all organic produce falls into the low- or very low-risk categories. Conventional items in the low or very low categories are essentially equivalent to organic.

Our No. 1 rule: Eat more produce! Though we believe that organic is always the best choice because it promotes sustainable agriculture, getting plenty of fruits and vegetables—even if you can’t obtain organic—takes precedence when it comes to your health.

Click on the chart to view a larger version.

Editor’s Note: This article also appeared in the May 2015 issue of Consumer Reports magazine.