National Geographic

by Maryn McKenna

By now, I suspect, most people concerned with the provenance of meat have a clear mental image of what concentrated production looks like.

By now, I suspect, most people concerned with the provenance of meat have a clear mental image of what concentrated production looks like.

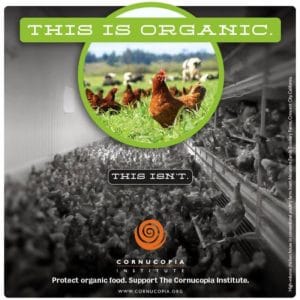

Take chicken, the meat we Americans eat more than any other: industrial chicken lives out its life in walled houses with tens of thousands of other birds, and balloons to its full size at only 6 weeks old. We also think we know what the alternative looks like: birds that are fed purer feed, given the chance to walk around on grass, and allowed to live weeks longer for meat chickens and years longer for laying hens.

We imagine that the industrial model and the sustainable alternative couldn’t be more different, and for the most part we would be right. With one important exception: Both begin life as eggs laid in a commercial hatchery and chicks delivered to the farm in their first day of life. And whether the chicken is the white-feathered, big-breasted Cornish Cross in millions of supermarket cases, or the sturdy, long-lived “red birds” of pastured producers, chances are that it can be traced back to hybrids owned by one of just a few hatchery companies scattered around the globe.

“These are corporate genetics from huge companies,” says Nigel Walker, proprietor of Eatwell Farm outside Dixon, Calif. “I’m embarrassed to say I am not even sure where my genetics come from right now.”

From the outside, Walker already appears to be doing everything right: He raises organic produce that is fertilized only by the efforts of his 2,600 laying hens, which every year break up and tend 20 acres of pasture out of the farm’s 105 acres. But the red-feathered layers he uses are proprietary hybrids, which he orders from a hatchery every time he needs to replace his stock.

The alternative would be to use standard-bred or heritage chicken, from types that have not been used in large-scale production since the poultry industry consolidated after World War II. Heritage chicken lines have survived in the poultry equivalent of seed saving, protected by just a few stubborn farmers and sustained in a few small hatcheries that serve backyard hobbyists and small farms. (The Livestock Conservancy maintains a list.)

Walker feels the loss of those open-source genetics acutely, because his egg business relies on a troubling side effect of it. When the chicken industry began hybridizing heritage lines, it divided the single category “chicken” into two types, broilers and layers, forcing them further apart with every generation. Eventually, broilers became meat birds that develop muscle quickly, but are killed so young that egg production is not possible, while layers were bred to maximize egg production instead of meat. To produce eggs, of course, a bird has to be female—which meant any male bird became instantly superfluous. It’s routine in layer breeding and egg production for male chicks to be killed soon after they hatch. (That’s an issue for food firms that use eggs as well.)

Check out this video challenging mayonnaise giant Best Foods, the maker of Hellman’s, about the fate of baby male chicks:

Walker, who has an in-demand CSA and a spot in San Francisco’s prestigious Ferry Plaza Farmers Market, worries that he’s inadvertently responsible for the sacrifice of hundreds of male chicks every year. He sees a way out, though: He could switch to raising a new—or rather, old—type of chicken, a heritage breed in which the females lay a decent amount of eggs but the males grow a respectable amount of meat. He won’t just be raising the heritage birds, though: He wants to return to the original farm model of breeding his own birds and incubating and hatching their eggs on his farm.

All he needs is a little help. Walker and Eatwell have launched a crowdfunding campaign on Barnraiser, a Kickstarter-like platform dedicated to sustainable food and farming projects. With half their time still to go, they’ve raised about half the needed money, which they estimate will total $20,000.

With those funds, Walker plans to begin replacing his “production red” layers with the historic breed Black Australorps. The hens will take 4-5 months to get to laying age, and then will lay eggs for two years, twice as long as commercial layers; the males will take 14-16 weeks to get heavy enough to be marketed for meat, two to three times as long as commercial broilers.

“The longer they live, the more feed they eat,” Walker said. “That’s why farmers switched to these new breeds of chicken in the 1950s: It got a chicken on every plate faster. You can’t blame the farmers then, because the government told them to ramp up production and produce as cheaply as they could.”

The funds will also pay for a new hatchery and brooders, along with nesting boxes that will automatically trap, weigh and record eggs from each breeding hen to track their reproductive success. Walker envisions using that data to develop an app that will help him, or any other farmer venturing into breeding their own chickens, to quickly identify his flock’s most promising members.

“We’ll constantly be identifying and selecting the best, which is really what farming is,” Walker told me. “It’s what farmers have done for hundreds of thousands of years. It’s only in the last 50 that we gave it up, and we hope to bring it back.”

This story is part of National Geographic’s special eight-month Future of Food series.