Tied to the Land and the Cows Who Graze It

Why Chaseholm Farm pivoted to 100% grass-fed

by Kestrel Burcham, Cornucopia’s Policy Director

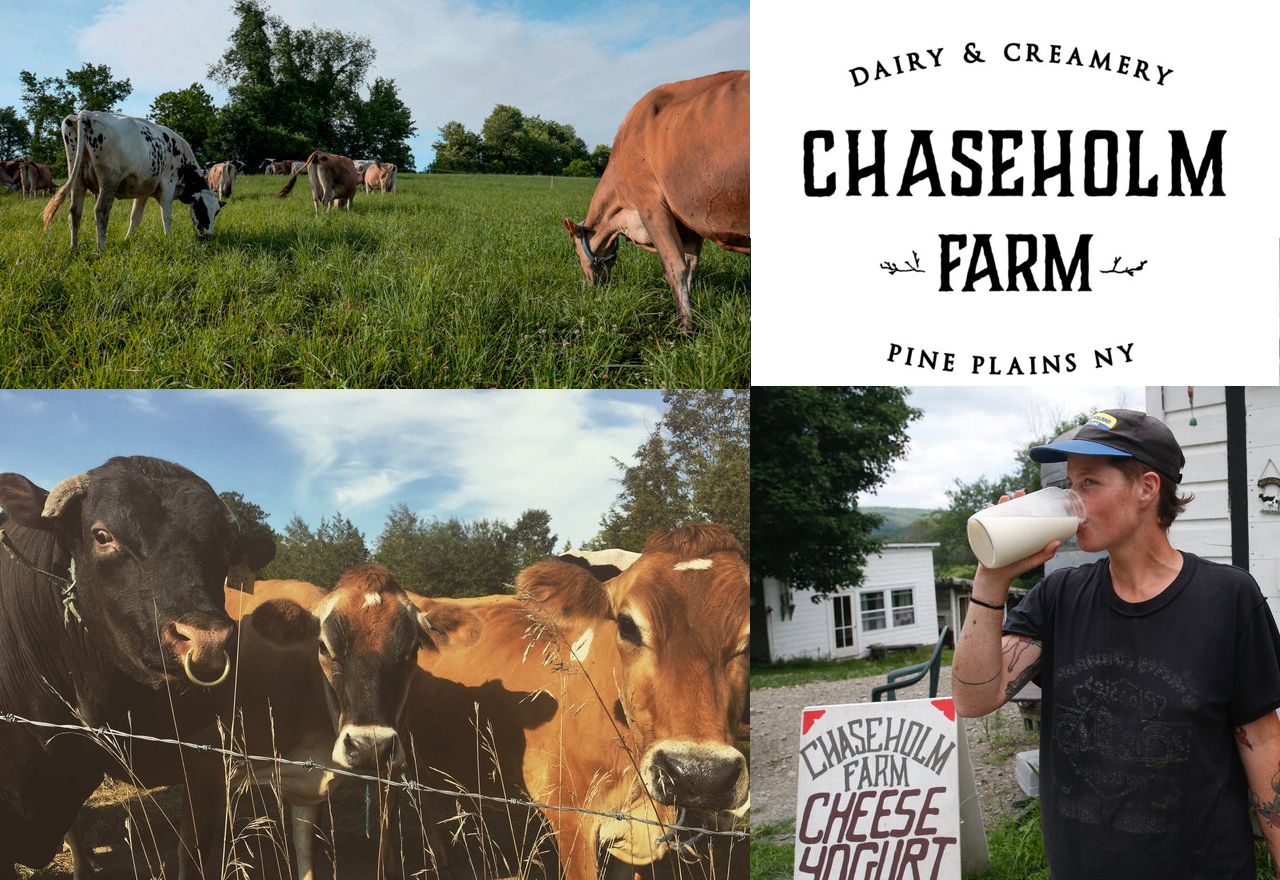

In 2013, Sarah Chase took over the day-to-day operations of Chaseholm Farm, the third-generation farm she’d worked on since childhood.

At the time, Chaseholm was a small conventional dairy whose cows ate corn silage, corn and soy grain, and dry hay. The cattle grazed on pasture in the summer and fall.

The true costs of production were not reflected in grocery store prices, and tight margins threatened the operation’s long-term viability.

Chaseholm pivoted in 2015, completely eliminating grain from the cows’ diet. Two years later, Pennsylvania Certified Organic certified the operation as organic and 100% grass fed. Today, the farm’s 100% grass-fed milk is sold at local farmers markets, Chaseholm’s farm store, and local stores; yogurt and grass-fed beef made from the culled dairy herd are sold direct to consumers.

With a dairy barn intentionally positioned next to the farm store, and popular burger nights that feature cattle grazing within eyesight of the grill, the goal is to tell a story about the food and the farm where it originated. “We are using animals for food and we provide a place to talk about it firsthand,” Sarah says.

A key theme of that narrative is the people who make this farm possible. Chaseholm is truly a family operation. Sarah’s parents, a constant source of advice and guidance, live on the farm. The bulk of Chaseholm’s milk goes to Sarah’s brother, Rory, to make cheese.

And Sarah’s partner, Jordan Schmidt (they married on the farm!), embodies Chaseholm’s vision for a “stronger, more just, and more ecologically supportive food system” in her work as the food program director at the North East Community Center. This community initiative in Millerton, New York ties support for a “sustainable regional farm system to work on increasing food access and community health,” Jordan says.

Chaseholm’s own contribution to the regional food economy is rooted in its decision to choose 100% grass-fed dairying, a practice that Sarah says is “good for the cows, good for human health, and good for the land.”

It’s also one that requires a substantial amount of patience and problem solving.

The original motivation for raising dairy animals on an all-grass diet was a desire to reduce inputs and long-term expenses. When the farm first stopped feeding grain, immediate benefits followed, but so did some challenges.

“There was a mismatch between the cows we had and a 100% grass-fed diet,” Sarah says. “It was very difficult to make any money at first because those cows were not thriving on pasture alone. It pushed us to really research genetics and breeding. Now we keep our own bull and manage our herd strictly for those that do well on a 100% grass-fed diet.”

Genetics is a critical piece of any grass-fed operation. Modern conventional dairies that push their cattle for high yields often use animals breeds that cannot meet their energy demands on forage alone, necessitating a diet high in concentrated feed like grain.

Sarah credits the farm’s current success to growing their own stored forage feeds. Chaseholm efficiently mows and wraps the feed in one 24-hour period—a practice referred to as “hay in a day”—resulting in stored feed that contains more energy for the cattle to utilize because the forage is fresh when baled. “Our own hay is much higher quality [than outside sources] and the cows flourish—even in the winter when they can’t be out in pasture,” Sarah says.

As the farm has evolved, so has an appreciation for the importance of soil health to the farm ecosystem. “Higher quality forage comes from good soil,” Sarah emphasizes.

Improving soil quality takes years and is more difficult to manage than other grass-based dairying concerns, Sarah notes. Guided by holistic management principles, Sarah works to encourage an active and healthy soil microbiology, so that soil can support healthy plants that can be grazed by cows, who happen to play a starring role in this production.

Using moveable electric fencing, cows are grazed and hay is harvested in a rotation that allows for periods of rest and recovery. This cycle of stress and rejuvenation attempts to mimic the grassland ecosystems where vast herds of wild herbivores constantly moved onto fresh grass—but on a much smaller scale.

This has all benefitted Chaseholm’s cattle, too. Vet bills and costs for health inputs are now nearly nonexistent. It comes as no surprise: When cattle are able to express their natural behavior and live in a low stress environment, health will almost always improve.

Ensuring that cattle continue to thrive on their 100% grass-fed diet requires continual culling of the herd for optimal genetics. Often, cows they plan to cull are finished on pasture, destined to become 100% grass-fed beef available at the farm store (along with steers born on-farm).

Selling the cattle for meat when their time is done on the farm further supports this farm system and completes a cycle that’s helping to sustain and nourish the community.